| Ralph's Homepage |  |

Diary - 1 - 2 - 3 - 4 - 5 | |||||||||||||||

| Military Homepage | Page: 2 | ||||||||||||||||

| PAGE ONE | |||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||

The Short Life and Death of Lieutenant Ralph. D. Doughty. M.C. WWI |

|||||||||||||||||

As told through his Five Military Diaries |

|||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||

Ralph’s five day-by-day diaries from the Great War dated from the 5th April 1915 to the 16th March 1917 |

|||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||

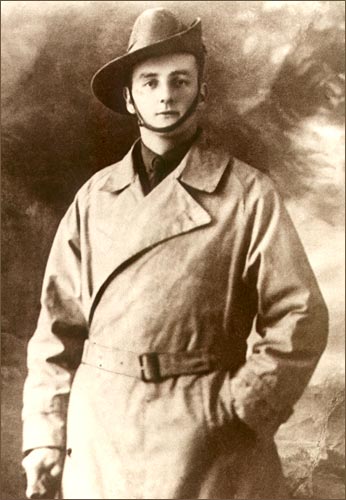

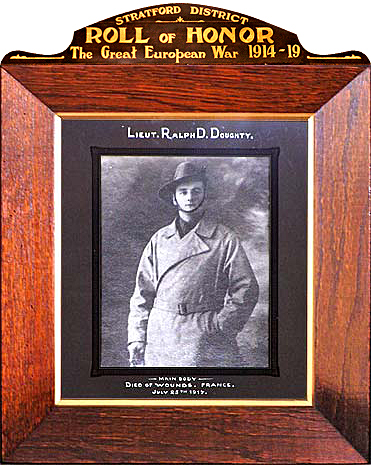

| Ralph Doughty in A.I.F uniform (studio portrait) | |||||||||||||||||

Foreword As a Kivell family member I have been very privileged to have seen and read the five war time diaries that my great, great uncle Lieutenant Ralph Dorschel Doughty wrote entries in during his military service in World War One, and I hope that this story on the life that he lived both here in New Zealand as well as during the time that he spent in Australia, and from there on to his service for the A.I.F. (Australian Imperial Force), will pay full respect to him and honour the life that he lived, being that he is such a respected family member. Our family was very fortunate that Ralph had had the inclination to take with him through his military service a means to record his personal experiences. This being in the form of five front line diaries that travelled with him through several campaigns. And that he also had had the fortitude and willingness to be able to make day-by-day entries in his diaries that so dramatically and vividly explain what the life of an artilleryman was like during WWI, and for this we will be forever thankful. 13th July 1915 Up at 4 am this morning. Turks counter attacked in force and gave us particular 'H' with vengeance. We've just stopped firing for the 3rd time this morning and as far as we can find out, the ground gained yesterday (1000yds) has been held by our chaps. 6 am. Had a glorious time. Started at 6:30 am, stopped firing at 9:10 pm. Worked the old gun til the springs broke and the piece itself was so hot that the bearings expanded with the heat and stopped the recoil. We fired 1160 rounds. My hands are burnt beautifully. Can hardly close my left. Got a whack on the knee which put me off the gun for half an hour but it's O.K. again. Heavy fighting all night. 8 pm. What a day. One of the hottest and best we've had. Got another 3 trenches in the centre, but don't know how the right got on. Have Clark, Adams, Cairns and 2 others all out of it. Later... Have just repulsed a mass attack by the Turks. Can't close my right hand, agony to write. We're all like niggers. Absolutely black with cordite smoke and dust. Like Mater (mother) to see me now. Throughout Ralph’s diaries he also made sure to mention his 'pals' as they all had a significant part to play in his military life. Be it beside him helping with the loading and firing of the 18lb battery gun, or spending time in a dugout playing cards around the billy while eating the daily rations (if there were any), to travelling by horseback down to the local village to gather supplies. But unfortunately Ralph also wrote entries in his diaries of their demise, either through illness or when they had sustained wounds while in action. Regret to have to record the death of one of our most liked boys. G.H. King (Kingy) was shot through the heart while bringing up ammunition. Buried "Kingy" under a hill in the rear of our position. Anyhow he met his death in the way we all hope to meet it if it is to come out here, "In action". One can only gain the utmost respect for every service person who is prepared to put themselves in harms way so that others may live without fear or tyranny, as Ralph did on many occasions, and we can only imagine what it was like to have gone through 'The Great War' but it is through the reading of Ralph’s diaries that you will gain a very good understanding of what it was like for him. From dawn till dusk and through many sleepless nights, from the heat and sands of Egypt, to the rain and snow of Gallipoli, and then onto the bloody battlefields of the Western Front and Passchendaele, Ralph’s set of diaries give a factual account of how he saw the war through his eyes, with every aspect and experience of artillery life placed onto the pages of his diaries so that by the time you read his final entry on the 16th March 1917 you will have gained an awareness of what his life was like during his nearly three years of active service. A whole generation of brave young men lost their lives when one 19 year old assassin from Slavic, fired two bullets. This occurred on the 28th June 1914 in Sarajevo, with the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand - heir to the throne of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, along with his wife Sophie. This was the catalyst which then led to the outbreak of World War I and went on to cost 15 million lives, with my great, great uncle being one of them, as sadly his fate was that on the 23rd July 1917 he sustained a gunshot wound to the abdomen while "in action" to then die of his wounds two days later. Ralph like so many other brave servicemen made the ultimate sacrifice for his country far, far away on the field of battle and will not be forgotten. R.I.P Peter Kivell |

|||||||||||||||||

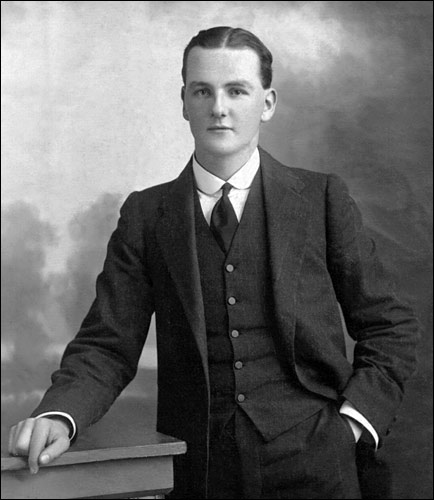

Ralphs Early Family History Ralph Dorschel Doughty was born in Stratford, New Zealand on the 1st October 1891 and was the youngest of eight children born to William and Susanna Doughty. He spent his early years growing up in Stratford and went through the public education system. On leaving school he went on to serve for five years with 'H' Battery in the New Zealand Field Artillery service, after which he left at the completion of his service. Ralph then got his first job as a warehouseman in Stratford but he soon decided that when he was old enough he would travel over to Australia to seek a job that was more rewarding and better paying, this he did in 1913 at the age 22. Ralph gained residence in 'Craignathan', Hayes Street, Neutral Bay, Sydney, New South Wales, but from this point onward little else is known about his personal life while living in Australia, things like whether he ever managed to get the job he went over the Tasman Sea for, or if he ever had a partner while living in Australia. It was not until Ralph entered the military service for the A.I.F. and records started to be kept that more information was gathered on his life. These military records were obtained from both the Australian National Archives, who supplied the family with a total of 93 documents, and from military information that was gathered from the A.I.F. project database. Ralph also supplied his own military records through the entries that he made in his diaries. They show that his life in the service of the A.I.F. was a complete, full and rewarding one. Ralph enlisted with the A.I.F. 1st F.A.B. 2nd Battery unit in Sydney on the 28th August 1914, and was allotted army number 193 (showing how close he was to being the first to sign up), he then began his initial training in Australia before embarking for overseas service from Sydney, N.S.W. aboard the Transport A8 Argyllshire on the 18th October 1914, to travel onto Egypt to complete his training. It was from here that Ralph started his first diary. |

|||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||

| Taken in Stratford | |||||||||||||||||

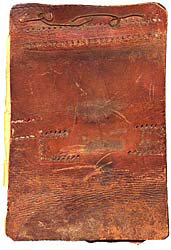

Ralphs Diary History Diary one, which is a large notepad with leather covers cut from a horse saddle and held together by a copper wire stitched through the spine, was started on the 5th April 1915, in Cairo, Egypt. It contains daily entries of Ralph’s time spent in the ‘Land of the Pharaohs’, and of his voyage over to Lemnos Island aboard the Transport ‘Indian’ where Ralph prepared himself for his first landing on the Gallipoli peninsular. This first diary was finished on the 15th September 1915, in a dugout, with Ralph deciding on who he was going to send his first diary back home to, this of course being ‘His Mother’.    24th April 1916 (Easter Monday) This afternoon we had our first "hate". Stuck in about a dozen rounds for luck. Our anti-aircraft guns brought down a Taube today. Sunday artillery duels the order of the day otherwise quiet. Its just 12 months back when we were all anxiously waiting for our first scrap, and here now after one year of scrapping we are considered quite veteran soldiers. Ralph made his last entry in diary four on the 11th August 1916, when he was in action around the areas of Le Val de Maison and Pozieres.  Ralphs last area of reference in his fifth diary was on the 11th March 1917, from the town of Albert (which is 4km south of Brussels), when he visited the officers club for afternoon tea, from here Ralph went on to make his last entry in his set of five diaries a few days later with what has to be a very appropriate and poignant ending for an artilleryman who had given his all since enlisting in Sydney back on the 28th August, 1914. 16th March 1917 Better day today. Very heavy bombardment on both left, right and centre. |

|||||||||||||||||

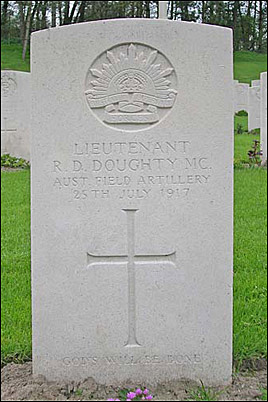

Enlistment and Diary dates Ralph enlisted on the 28th August 1914 to die of wounds received in battle on the 25th July, 1917, this being a total of 2 years, 10 months, and 29 days of active service. Ralph had starting his diaries on the 5th April 1915 in Egypt, and ending them in Passchendaele on the 16th March 1917. This covered a total of 1 year, 10 months, and 46 days through three major campaigns of Gallipoli, the Western Front and finally Passchendaele. |

|||||||||||||||||

Ralphs Promotional Record Ralph’s progress through the ranks started when he initially enlisted as an artilleryman on the 28th August 1914 then during the Gallipoli campaign he was appointed to Acting Corporal on the 20th June 1915 to be then made Provisional Corporal on the same day. On the 12th March 1916 on Ralphs arrival in Tel El Kebir, Egypt he was promoted to 2nd Lieutenant and was then finally promoted to 1st Lieutenant on the 13th June 1916 when he was in action at Flanders Fields as shown below from his entry that have been extracted from his diary. 9th July 1916 R.O.O today. Went out exercising horses this morning. Afterwards jumped some of the horses. Several visits from Taubes today. The Colonel paid us a visit today and brought with him the news that my 2nd star has been confirmed. So from now on I hold the rank of a First Lieutenant. What a Dorg. Ralph was also awarded his Military Cross on the 9th April 1917, for his action at HERMIES (which is situated 16km SE of Arras). Lieutenant Ralph Dorchel DOUGHTY 'For conspicuous gallantry and devotion to duty when acting as Forward Observation officer. He sent back most valuable information and was responsible for bringing artillery fire to bear on the enemy at a critical time.' Source: 'Republished in the Commonwealth Gazette' Date: 11th October 1917. |

|||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||

|

The Military Cross M.C. was instituted in 1918. It is awarded to junior officers and senior non commissioned officers of the Army for courage and devotion to duty on active service. Anzac Commemorative Medallion was given to every Anzac soldier who served on the Gallipoli Peninsula, or was in direct support of operations there, or his family if he did not survive until into the late 1960s - was entitled to be issued with the Anzac Commemorative Medallion. The 1914 - 15 Star this medal was awarded to servicemen and servicewomen who served between August 1914 and December 1915, provided they had not qualified for the 1914 Star. This included service at Gallipoli. The British War Medal this medal was instituted in 1919 to recognise the successful conclusion of the 1914 - 18 War. Its coverage was later extended to recognise service until 1920, mainly in mine clearing operations at sea. The Victory Medal this medal was issued to all those who had already qualified for the 1914 or 1914-15 Stars, and to most persons who had already qualified for the British War Medal. The Victory Medal is distinguished by its unique 'double rainbow' ribbon. Approximately 6 million of these medals were issued to military personnel from the British Empire. |

|||||||||||||||||

Medical Record Along with so many other servicemen at Gallipoli (and elsewhere) Ralph suffered from Pyrexia (severe fever). So on the 27th July 1915 he was evacuated back to a hospital ship and then onto Lemnos Island to recover. He returned to duty, although not back to 100% health on the 5th August 1915 when he was landed back on ‘W’ beach in the early hours of the morning and was then back into action later that same evening. Ralph received an injury when he was wounded in action at Flers, France on the 18th November 1916 after a shell explosion buried him and he sustained a concussion blast in the head and an injury to his shoulder and had to be admitted to the 38th Casualty Clearing Station before being transferred to the Ambulance Train No 26 on the 19th November 1916. He was admitted to No 8 General Hospital, Rouen where it was found he was suffering from Trench Feet, which is an infection of the feet caused by cold, wet and insanitary conditions. From there he was transferred back to England on the 21st November 1916 and admitted to the 3rd London General Hospital, Wandsworth on the 22nd November 1916, for recuperation. After recovering from his injuries Ralph was discharged to No 1 Command Depot, Perham Downs on the 27th December 1916 and was marched out to the Reserve Brigade, Australian Artillery at Heytesbury on the 21st January 1917 and preceded back overseas to France on the 31st January 1917 to rejoin the 9th Battery, 3rd Field Artillery Brigade on the 9th February 1917. Ralph was again wounded in action at Passchendaele, Belgium, on the 23rd July 1917 when he sustained a gunshot wound to the abdomen and was admitted to the 91st Field Ambulance Station. But this time lady luck was not with him and he did not recover from his wounds and died two days later on the 25th July 1917 at the age of 26. Ralph was laid to rest at Coxyde Military Cemetery, Plot I, Row F, Grave No 20, Belgium. |

|||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||

| His Duty Done | |||||||||||||||||

|

Introduction From an article published in the Sunday Express April 1983, New Plymouth, by Murray Moorehead.

The ranks of the old Gallipoli veterans are thinned now to a mere handful, and there would not be much more than a decade left for anyone to get to know, in person, a man who could proudly claim to have played a part in the forging of the great Anzac brotherhood. They have certainly had full lives, these dogged veterans. Those still with us on Anzac Day two years hence will be able to look over 70 long and eventful years since they helped make history on the slopes of an arid and inhospitable peninsula which most of the world had never heard of before. But it is not only the living whom we may get to know with some intimacy. To the members of the Kivell family in New Plymouth, a man named Ralph Doughty remains someone more than merely some distant ancestor who died in a war that was over long before most of them were born. Ralph Doughty is, in his way, still very much a part of the family. New generations of Kivells feel that they know him almost as intimately as those to whom he said cheery goodbyes as he left Taranaki to seek his fortune in Australia shortly before the Great War broke out. Ralph Doughty was one of those gems of men who kept a diary. He was not unique in that, of course; army records and museums are full of war diaries. But two things make Doughty's record of the war stand out. The first is that unlike most others he kept a record of every day of his war, even the dull days that other diarists might have skipped over, and even had days - apart from those which, through sickness or wounds, he had no recollection. The second is that his diary was born to be treasured by his family. From the oldest to the youngest, members of the family know this man whose portrait hangs in the Stratford War Memorial arcade, for he reminisces with them through the entries in his diary as surely as if he were still with them as one of the last of the old brigade. The record of Ralph Doughty's war begins in a small pocket pad, protected inside a cover of thick leather and with the pages fixed firmly in place with a weaving of thin wire. It is not easy to follow, even though it is written in a neat and flowing hand. The entries are in pencil and are written to take advantage of every square millimetre of the precious paper. A member of the family is currently working hard to translate the handwriting into a more easily readable typescript. With the pad filled on both sides of each page by the end of November 1915, the chronicle continued in a collection of notebooks, day by historic day, until July 23rd, 1917 when Lady Luck, who had been right at his side on so many occasions during the past 26 months, chanced to be looking the other way. Ralph Doughty died from his wounds on July 25th and was buried at Coxyde [Cosayde] Military Cemetery in Belgium. He died a hero, having been awarded the Military Cross just two months earlier for gallantry.

Stratford He died an officer and a hero, but he began his war as the most ordinary of men, the most typical of Anzac soldiers. He was born in Stratford and was 22 years of age when he joined the Australian Army in Sydney just a few days after the declaration of war. As a member of the 2nd Battery, 3rd Field Artillery Brigade. Doughty began his diary on April 5th, 1915. Like every other man from down under who landed in Egypt in those heady pre-Gallipoli days, Doughty was itching to get into action. His remarks on his first day on which elements of the Australian and New Zealand Army Corps began their first move from their camps near the Pyramids towards the eventual landing at Gallipoli, show that clearly: "We got embarkation orders thank God. So here's to it and may our little flutter which we are about to have tend in some way to weight the balance against this Most Satanic Majesty The Kaiser. Bravado The landing was still more than 20 days away and the move northwards was broken by an interlude in Alexandria. Poor Alexandria! It was a boom time for the Egyptians as the young soldiers spent their money with the bravado and abandonment of those about to go into action for the first time. But while they spent they also gave birth to those great wealths of yarns that every man of both the 1st and 2nd N.Z.E.F. had to tell about a soldier's life in Egypt. A few entries like: "Had an argument with a cabbie, just to show our independence" and "Had supper at a restaurant . . . they came of second best!" give the gist of just what the poor Egyptian had to grin and bear while he raked in the skekels. Doughty's ship sailed from Alexandria on the 10th. "Don't know where we're off to. Think it's the Dardanelles." The gunners missed out on the Landing. They were off Gallipoli with the rest of the fleet and fully expected to go ashore on the 25th. But, on the following day: "On getting to the shore received orders to go back as the landing was too crowded. Didn't we curse! I'd like to have 5 minutes with the officer who handed out that order." Nine days were spent at sea, learning what it was like to he a sailor on the receiving end of the heavy and accurate Turkish gunfire before getting ashore at last on May 4th. Perhaps one of the most interesting facets of the Gallipoli campaign was the mental response of those who served on that hellish peninsula. Dare one even consider whether their grandsons would have been able to serve in the same conditions without finishing up psychiatric wrecks? Accepted Could any modern soldier kill and be killed as the men of Gallipoli did, live on the verge of death for as long as they did in such charnel house conditions, regard their enemies with such comradely respect as they did the "lurk, leave the place, sick or wounded, with as much reluctance, and finally abandon a lost cause with as much heartbreak? Could such horrors be accepted today as "part of the game" and recorded as the Anzacs recorded them, in such a matter of fact way? The ordinary Anzac soldier was not a clever man, neither interested in nor particularly gifted at composing words to cover true feelings. He wrote down what he thought. His relishing of his role in the Great Adventure was as overt and immodest as it was possible to be. He saw no need to feign reluctance to fight or to take a modest stance on expressing his feelings about King, Empire and Country. Brashness Brashness, flippancy and the sense of adventure might have been understandable in the writings of the Gallipoli men at the beginning, but the same attitudes are to be found in their words right up the end. On June 7 Doughty mused in a casual way about a new type of shell fired by 'our friends'. One small J extract from the musing: "One has just come over and landed in front of the battery. Several chaps have been blown out. The funny thing about this shell is that it just strolls through the air just like the hum of an aeroplane motor but the burst is terrific . . . one has just struck on the road and out of 30 men 27 are down..." He wrote in equally casual manner just a few days later of a way of dealing with one of the greatest dangers to life; "This evening we captured four snipers. Had a firing party, the only thing was that we had the rifles, they didn't. Only way to deal with these chaps, although they are brave men." The attitude was little changed as far on as November 25th when he described the result of a breakthrough by a party of Turkish soldiers: "They were met in Monash Gully by some of our lads. The Turks, not that lads, went west" Atmosphere In his writings Ralph Doughty displays a talent for being able to create atmosphere and to be able to present a clear picture of what he is trying to describe with the greatest economy of words. There could be no one day's entry which might be singled out as an example of the average day on Gallipoli. There was really no such thing. But perhaps if one were seeking an example of what a day in action was like, the entry for July 13th would do nicely: "Up at 4am. Turks counter attacked in force .. . we've just stopped firing for the third time this morning, 6am. Had a glorious time . . . Started again at 6.30am, stopped firing at 9.10pm. Worked the old gun till the springs broke and the piece itself was that hot that the bearings expanded with the heat and stopped the recoil. We fired 1160 rounds. My hands are burnt beautifully. Can hardly close my left. Got a whack on the knee which put me off the gun for half and hour, but it's OK again. "What a day. One of the hottest and best we've had . .. Have just repulsed another massed attack by the Turks. Can't close my right hand, agony to write. We're all .. . absolutely black with cordite smoke and dust. Like Mater to see me now!" It has already been mentioned that Lady Luck spent quite a bit of time with Ralph Doughty on Gallipoli. Some examples: June 4: "A shell burst just in front . . , knocked me a bit silly but didn't hurt much. July 24th (The Turks) lobbed one just 12 yards away. We all got covered in sand and stuff but no damage done. Were all going to take a ticket in Tatts when we get back." And August 22nd "Nearly had a trip to Alexandria, by the way, per shrapnel." Doughty survived the bullets and shrapnel, but like almost every man who was there from start to finish, he couldn't escape the scourge of sickness. It is a chilling exercise to be able to follow the record of his illness through the long succession of daily entries. It must have begun on July 17th "We are quartered in a - of a hole! The trench for close on a mile is full of dead Turks with but 6 ins of earth over them. The odour is, well, I won't try to describe it, but it's no EAU DE COLOGNE! And we're here for 48 hours. How romantic!" Reluctant Not surprisingly, his sickness began soon afterwards, but it was not until July 28th that he collapsed and had to submit to evacuation. His was typical of the Anzac spirit. Doughty was reluctant to go, and once off, reluctant to stay off. He wrote on July 30th (On Lemnos) "Find that this hospital is . . . British. Applied for a transfer to our Australian hospital but was refused (only a few yards away). Before I'll come away again to an English field hospital they'll have to shoot me. I am cutting out a few days here. Won't record anything. Want to forget this spasm." On August 4th he was "Off back again, thank God. Feeling pretty rotten but I'll take my chance in getting better hack there!" Violence Doughty's unit was evacuated from Gallipoli on December 8th, first to Lemnos where the troops became involved in a series of inter-unit rugby matches which, as far as violence was concerned, seemed to lose little in comparison with some of the event of the past eight months. "Look at me. Both knees minus skin, ditto ankle and nose and a swollen lip. Watson got a bump on the head which knocked him silly for 3 hrs and England got a broken rib. Still it was a ripping match. We beat the Engineers 9 to 0." This period of time is contained in the second diary. The third diary commenced in March 1916 on the eve of the next Great Adventure, the one which would, for Ralph Doughty, last but 16 months. Even now, after eight months of what most historians would agree on as being close to the ultimate in hellish campaigns, the old Anzac spirit remained unquenched: "Hur-blooming-ray. Marching orders at last and as pleased as a cat with two tails. This time I leave Egypt as a blooming officer. Am feeling awfully fit, so watch out somebody!" Murray Moorehead. |

|||||||||||||||||

|

Dedication This dedication was written by E. S. Ellison, (Bill Allison) the writer of two New Zealand books; Kiwi at Large, and Kiwi Vagabond. Errol served in World War Two beside Charles Upham V.C. and bar. Dear Peter,

Thank you so much for giving me the opportunity to read these truly wonderful diary’s written by your great, great uncle Lieutenant R. D. Doughty M.C. They are truly a most unique set of interesting diaries, and are well worthy of publication. The writer doesn't set out to glorify himself or war and writes in such a straight forward style, as though he’s writing a letter to family or close friends. The very writing material on which the young Lieutenant writer uses is unusual - the leather horse harness. It also seems a though he wanted the horses to take a part in the diaries, for he began his military life with the horses; but he also took a keen and active interest in all aspects of a gunner’s life and it seems his officers soon recognised his worth and his courage, for he soon was made a 1st Lieutenant. He certainly earned his rank and his Military Cross. His diary notes are certainly the most interesting ones that I have read, they give such a vivid account of real life and death on ‘Gallipoli’ and in ‘Flanders fields’. He doesn’t set out to impress, and yet no other diary note’s I’ve read are as true and vivid as his. And I learned from his diary much more than from many of the other histories that I’ve read, until I read his diaries I was not aware that so many aircraft (on both sides) were used, and so many submarines, nor did I realise that so many other nationalities were involved apart from the British, the ANZACS, the Turks, and of course the Germans, I was surprised to read that Greek troops (some thousands) were also involved, and the French, and French-Africa troops. Then of course from the hell of ‘Gallipoli’ he went on to serve in the harrowing mud of Ypres, then to his death in the shambles of ‘Passchendaele’. He had a very, very long and hard war. His M.C. was well earned. I should think he meant to part his diary notes home, for he probably would not have much time to write letters. And thank you again for giving me the opportunity to read these truly unique diaries. Bill Allison |

|||||||||||||||||

|

Acknowledgments

I would first like to acknowledge the assistance that Jane Webster and Gary Danvers gave with the transcribing of Ralph’s five diaries. Without their skill and dedication the life that Ralph Doughty experienced during WWI would have remained on the pages of his diaries in an unreadable format. It is with gratitude that we thank them both, knowing that it would have taken many long hours of hard work to transcribe the diaries, and for their effort we thank them both very much. I would also like to personally thank Jane for allowing the family to acquire the forth diary which had been missing for many years. It’s existence was only discovered through share luck and now completes the series of five diaries that Ralph was known to have written. I would like to thank the National Archives of Australia for the care and attention they have given in preserving Ralphs military records during the various Field Artillery Brigades that he was in. From his enlistment with the 2nd Battery, 1st Field Artillery Brigade through to the 9th Battery, 3rd Field Artillery Brigade. And finally I would like to thank Ralph for leaving such a legacy for current and future generations to read. The information and knowledge that is gained through the reading of the diaries, fully explains just what the life as an artilleryman was like throughout WWI. You will not be forgotten |

|||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||

| CROSS OF SACRIFICE IN REMEMBRANCE OF THOSE WHO GAVE THEIR LIVES FOR OUR COUNTRY |

|||||||||||||||||

| Donated to the Citizens of Stratford by members of the Stratford and District Returned Services Association Dedicated 10th November 1957 |

|||||||||||||||||

|

Appearance of Ralphs Diaries

It is not only a miracle that all five diaries have made it back from the front lines of several campaigns intact, but also of how the diaries came into the hands of my father that needs to be told. This starts with my father as a small boy and this is his story below. I seem to remember as a child looking at books and maps relating to the Gallipoli campaign and being told that we had a relative who served there. Ralph’s connection to me is that my maternal Grandmother was Ralph’s sister; there were four sisters and two brothers in the family. Later in life I was given a leather covered diary (diary one). I was never aware of any other diaries until my father had passed away. Then one day my mother said to me that as I had the leather bound diary that I had better have the others. She then gave me three more diaries written by Ralph during his service in World War One (these being diaries two, three and five). Some years later, when as a member of the New Plymouth R.S.A. I was told that there was a letter for me in our club letter rack. The lead up to this letter was that there had been a family reunion for the members of the Ward family (one of my grandmothers sisters had married a Ward). Ralph Doughty Ward, who was named after Ralph Doughty, and who was later to become the New Plymouth R.S.A. President had attended a family reunion and had met a Jane Webster (Ralph Wards niece). Incredibly while speaking to Ralph she had told him that she had in her possession another one of Ralph Doughty’s diaries (diary four, the long missing diary). She was then told that there was a chap in New Plymouth (myself) who also had one. Contact was then made between Jane and myself and I was able to tell her that there was more than one diary. We arranged a get together in New Plymouth, and her diary slotted neatly into a gap between diary three and five. We then arranged that I would take all the diaries to her place and through some great work by Jane Webster and Gary Danvers, the whole set of five diaries were transcribed and typed up into a readable format. Tony Kivell |

|||||||||||||||||

|

Wreath placed on ANZAC day Coxyde Military Cemetery, Belgium. |

|||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||

|

They shall grow not old As we that are left grow old Age shall not weary them Nor the years condemn At the going down of the sun And in the morning We will remember them |

|||||||||||||||||

|

Information on the Diaries

With the original transcribing of the diaries some of the words have eluded the transcribers. So they have just left as a series of ... or there may be a guess as in what the entry was [Gillagan?]. Ralph also made his own comments through his diaries and these were round bracketed (thus). Also explanations and expansions of slang terms were indicated similar to the guesses but without the question mark. Some locations in and around the areas of the Western Front and Passchendaele have also been hard to interpret so these have had to be [guessed?].

After I had read Ralph’s diaries several times I have filled in some of the gaps that were unfortunately to difficult to transcribe. These gaps were due to several reasons. |

|||||||||||||||||

| In the Hall of Remembrance | |||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||

| Stratford, Taranaki, New Zealand | |||||||||||||||||

| Ralph's Homepage |  |

Diary - 1 - 2 - 3 - 4 - 5 | |||||||||||||||